Tracing science-technology-linkages through patent in-text references

The contribution of science to technological innovation is subject of ongoing debate. In a recent study, our authors investigated how the value of patents depends on the scientific articles referenced and what role aspects such as basicness, novelty, and interdisciplinarity play in this.

The relationship between science and technology

There is a recurrent debate about how useful science is for technological innovation. However, science is heterogenous, and some types of scientific outputs may contribute disproportionately to technology. We lack empirical evidence to assess whether more applied and interdisciplinary research is more directly useful for technology, characteristics which are also believed to be key features of research that is useful for society. We also do not know whether science’s autonomous pursuit of novelty and peer recognition might be at odds with the policy goal of making science more useful for the economy and society. Therefore, we studied how basicness, interdisciplinarity, novelty, and scientific citations are associated with patent value.

How to trace science-technology-linkages?

To answer our research question, we first need to trace science-technology-linkages. References in patents to science provide a paper trail of knowledge flow, and scholars have long exploited these references for science and technology studies. However, the state-of-the-art practice uses almost exclusively patent front-page references but ignores patent in-text references. Patent front-page references are listed on the front page of the patent document, reporting prior documents that are relevant for assessing the patentability of the invention. Patent in-text references are embedded in the full text of the patent, very similar to references in academic papers (see Figure 1). Recent studies have suggested that patent in-text reference is a better indication of knowledge flow than front-page references.

However, extracting patent in-text references is a formidable task, as they are embedded in the running text without structural cues. We approach this problem as a sequence labeling task. We train BERT-based models to automatically classify each word as (B) beginning of a reference, (I) inside a reference, or (O) outside a reference. These labels then enable us to extract reference strings from the patent text. Subsequently, we match the extracted references to individual Web of Science (WoS) journal articles using regular expressions and pattern matching. We apply this method to 33,337 USPTO biotech utility patents granted between 2006 and 2010 and extracted their 860,879 in-text and 637,570 front-page references to WoS articles.

One first observation is the remarkably low overlap between patent front-page and in-text references. In total, 173,281 references appear both in the text and on the front page of the same patent, which accounts for only 20% of all in-text references and 27% of all front-page references (Figure 2). This low overlap suggests that in-text and front-page references embody different types of information. Accordingly, using different types of references to study science-technology-linkages may lead to very different conclusions.

How does patents’ value depend on the characteristics of their referenced scientific articles?

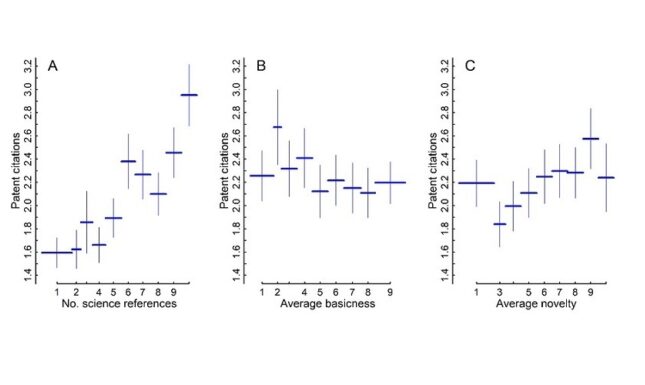

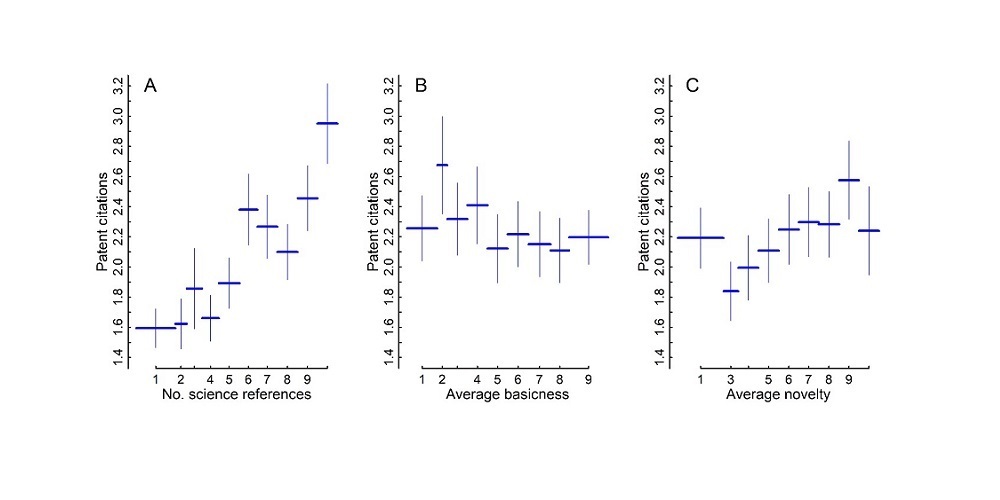

We answer this question using the dataset of 33,337 USPTO biotech utility patents and their 860,879 in-text references to WoS articles. We measure patent value by the number of times that a patent is cited by future patents. Combining Negative Binomial regressions and non-parametric visualizations, we first observe that patents citing more scientific articles also receive more patent citations than patents citing fewer or no scientific articles in the same issuing year and technology class (Figure 3A). Using a basicness measure based on PubMed MeSH terms (basicness = 3 if a paper has only cell- or animal-related MeSH terms, 2 if both cell-/animal-related and human-related MeSH terms, and 1 if only human-related MeSH terms), we also find an inverted U-shaped effect of basicness on patent citations, when comparing patents with the same number of science references and in the same issuing year and technology class (Figure 3B). In addition, we identify novel publications as the ones that make unprecedented journal combinations in its references. We found that novelty displays a discontinuous and nonlinear effect, suggesting a structural change between patents building on novel science and those which do not (Figure 3C). We do not find clear effects of interdisciplinarity or scientific citations.

What are the implications?

Regarding science policy, our result partly supports recent advocating for application-oriented research. On the other hand, it warns that completely dismissing basic research is detrimental as the association between basicness and patent value is not a simple negative relation. Our results do not provide evidence that interdisciplinary research is the key for making science more useful for technological innovation. With respect to novelty, our results do not provide a clear message as to whether science policy should support novel or non-novel research, as the association between novelty and patent value is rather complex. Our results do suggest that novelty plays a special role for technological innovation and warns about potential disruptions and uncertainties that sourcing novel science can bring about. In terms of scientific citations, we do not observe a positive, but neither a negative association between them and patent citations. This means that although the quality standard or taste might be different between science and technology, they are not at war with each other.

For studies using patent references, the low overlap between patent front-page and in-text references, and more importantly the fact that they produce different analytical results, warns about a potential threat to validity due to data source. This means that we need to better understand how references are being generated in patents before we can determine which type of references to use in different research contexts.

Our full study, available as a preprint, goes into more detail and provides further analyses on the topics covered. If you are interested in this, please feel free to find out more.

0 Comments

Add a comment