The unintended consequences of task specialization in research careers

Researchers collaborate specializing in specific tasks. However, the research evaluation system only rewards specific profiles of researchers, threatening the diversity of the science ecosystem.

In this blog post we discuss recent findings on the relation between career trajectories and task specialization. Research careers are commonly envisioned in evaluation schemes as homogeneous pathways in which individuals have to take a series of steps to advance. In each of these steps, researchers must comply with certain expectations, usually so embedded into our way of thinking of scientists that many countries and supranational agencies even explicitly address what is expected of individuals at each stage. The rationale behind this is to ensure that career paths align with academic positions, and describe the whole process from apprentice to colleague.

Examples of such simplified vision of research careers can be found for instance in the Research Profiles defined by the European Commission (Figure 1), in which four stages are defined along with the expectations and requirements needed to reach each of them. In the description of such profiles words such as excellence and leadership are common, in many cases even used as interchangeable, sending the message that a hierarchical structure is expected in research teams, and that this hierarchical structure is directly linked to seniority. But one might question to what extent those expectations match reality. Is there such a strong link between career stages and researcher profiles? And what happens when researchers deviate from such expected roles?

In this post we discuss our findings after designing a model based on a machine learning algorithm to predict the probability of scientists to contribute in specific ways over their complete career, based on the contribution statements of a seed of their publications. Based on our predictions we were able to identify different archetypes of researchers across career stages. We distinguished between four career stages and compared differences between archetypes of researchers based on their career length, productivity, citation impact and gender. We observed differences on career length based on the archetype, plus gender differences on the type of profile researchers have at their early-career.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the career stages designed by the European Commission along with the expectations at each state, and an attempt at aligning them in a timeline.

Distribution of labour and archetypes

There is increasing evidence that scientists tend to specialize on specific tasks during their career in order to be more efficient when collaborating to distribute the work among co-authors. Authors’ contribution to publications is commonly associated with their position in author order, signaling middle positions as those conducting more technical and specialised (e.g., applying advanced methodologies) tasks, while first and last positions are commonly reserved to those leading the work. Of course, if the unique career path ideal resembles reality, one would expect junior scientists to be earning their stripes first in middle positions and contributing with technical expertise and later on moving towards leading roles. But in a recent study published in PNAS, the authors suggested that there is an increasing number of middle authors who never reach these leading positions, and furthermore, that their presence is crucial to ensure scientific progress. But, is their middle position related to task specialisation as they seemed to imply?

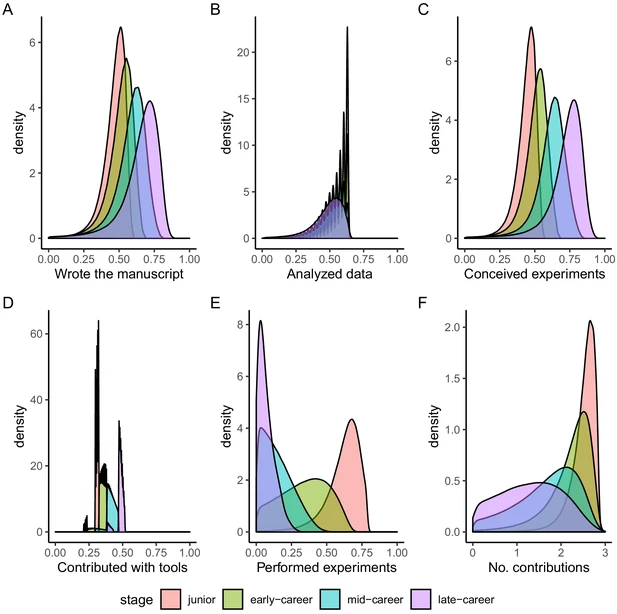

To answer this question, we trained a prediction model using a dataset of over 70,000 publications from PLOS journals (all data has been made openly accessible). This model used bibliographic and bibliometric variables to predict the probability of a given author to conduct a given contribution. We then retrieved the complete publication history of over 200,000 researchers from the original dataset, and predicted the probability of contributions for each paper and author. Figure 2 shows the distribution of our predicted probabilities distinguished by the career stage in which researchers conduct each contribution.

Figure 2. Distribution of predicted probabilities of contributions for the complete history of researchers.

Just from inspecting these distributions, we do observe that some contributions are indeed more aligned with career stages than others, but that such distinction is not as clear as one would imagine. Still, we are not able to discern if individuals consistently carry on the same contributions when collaborating.

This is where we used Robust Archetypal Analysis, a technique that identifies archetypes, which accentuates specific features of individuals’ population. To our surprise we found consistent similarities between archetypes across stages, with two archetypes at the junior stage (specialized and supporting), three at the early- and mid-career stages (leader, specialized and supporting), and two at the late-career stage (leader and supporting). Leader profiles are characterized by high probabilities on writing the paper and conceiving and designing the study. Specialized archetypes are researchers who are in charge of performing experiments, but also may play a role on the writing, conception of the study and analysis of data. Finally, supporting authors conduct more marginal contributions to papers.

Career trajectories, productivity, impact and gender

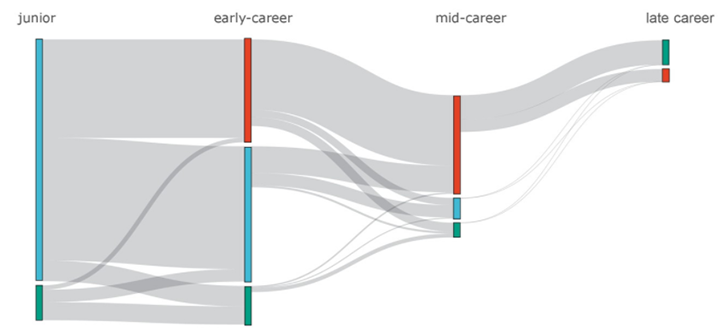

The archetypal analysis provides evidence that scientists specialize on specific tasks during their careers, but do they exhibit the same profile during their whole trajectory? Are there differences in their performance? Do we observe differences by gender on the profile of scientists? To answer these questions, an archetype was assigned to each researcher, at each career stage, and the trajectories of archetypes inspected. Figure 3 shows these flows. The first thing we notice is that a researcher’s profile seems to influence their possibility of making it to the next stage. A larger share of leaders make it to the next stage, followed by specialized and last, supporting. Furthermore, leader profiles seem to be more versatile than the rest, that is, they seem to more easily shift from the leading profile to any of the other two.

Figure 3. Trajectories of scientists analyzed by archetype. Blue shows the specialized profile; green, supporting; and red, leader.

In terms of productivity and citations however, leaders and supporters show a better performance than specialists. This means that evaluation based on productivity and citation metrics may be undermining specific and indeed valuable profiles of researchers. But most worryingly, we find that there are gender differences at the early-career stage. That is, most male scientists at this stage show either a specialized or leader profile, while for women there is a strong bias towards the former. At this critical stage, this could be affecting women’s career prospects in a definite way, as their performance is hindered by the type of tasks they perform, as our results suggest.

Revising assumptions and looking forward

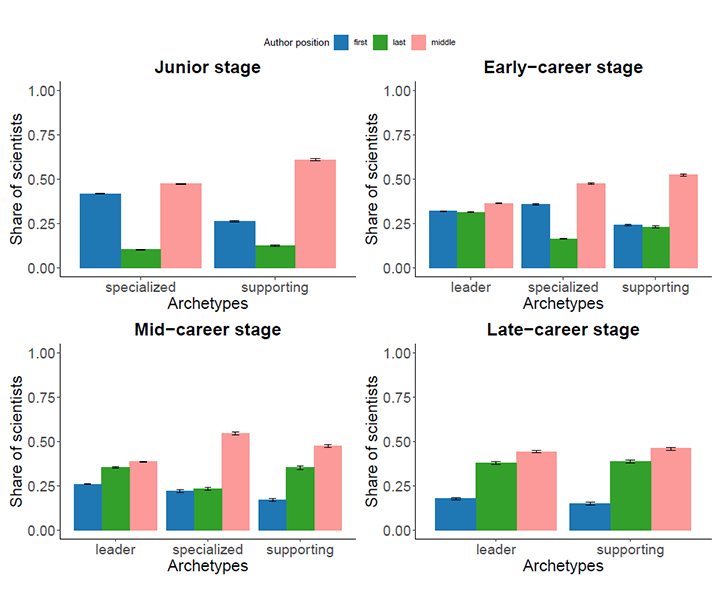

This study is part of the ‘Unveiling the Ecosystem of Science’ project, in which we aim to systematically analyze the diversity of profiles in science, with the hope of devising methodological tools that can improve current evaluation systems. With this specific study we also look into the potential of surpassing the well-known limitations of authorship by going beyond equal attribution of credit among authors. An example of this can be observed in Figure 4, where we look at the share of scientists by archetype and career stage publishing either as first, middle or last author. Here we observe that neither seniority nor archetype are always the ruling criteria as normally assumed.

Figure 4. Share of scientists by career stage and archetype based on their author order in publications.

With this study we hope to continue the conversation into looking at diversity in science. How to design tools that can improve our understanding of this diversity, and design evaluation tools that can contribute to maximize efforts and ensure an hospitable work environment for researchers. We need to ensure that evaluations do not add constraints and stress that can destabilize the ecosystem of science. Narrow definitions of excellence and poorly designed research careers, not only work against the progress of science, but affect attitudes towards success and failure, as it “generate(s) hubris and anxiety among the winners and humiliation and resentment among the losers”.

0 Comments

Add a comment