Attention for science in step with policy? The case of school closures during COVID-19

The closing and opening of schools during the COVID-19 pandemic caused much debate. How was scientific evidence used in the ensuing public discussion? Our authors searched for evidence in the news and on Twitter and looked at three countries in particular: the Netherlands, Spain, and South Africa.

One of the many puzzles of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the extent to which children are vulnerable to and spreaders of the virus. Fewer infection rates have been reported in children compared with adults, as have milder symptoms. But the infection rate in children is biased, given the testing policies in many countries. Schools received distinct attention early on in the pandemic – closing schools was among the first measures taken worldwide to reduce the spread of the virus. By March 31, 2020, schools in 193 countries were closed. Likewise, reopening schools has been part of the first steps in the easing of lockdown restrictions. With no definite scientific consensus regarding children’s role in the transmission of the virus, decisions on the reopening of schools could not be deferred.

Given the uncertainty, we were curious about how scientific information was used in the public debates around the closing and opening of schools. In a recent case study, we looked at Spain, South Africa, and the Netherlands, each of which introduced different measures. (At the time of the writing of our study in early December 2020, the school closings in winter 2020/2021 still had to happen.)

Our point of departure was the COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19) and the World Health Organization (WHO) COVID-19 Global literature on coronavirus disease database as of October 15, 2020. In this set, we identified 5,713 publications that were related to the key-terms ‘children’ and ‘schools’. In data provided by Altmetric.com, we found news media items and tweets from the three countries that included a mention of any of these publications (Table 1).

| Spain | South Africa | Netherlands | |

| News articles | 188 | 74 | 133 |

| Scientific publications mentioned in news articles | 74 | 69 | 76 |

| Tweets | 15,603 | 992 | 1,277 |

| Publications mentioned in tweets | 852 | 272 | 214 |

Table 1. Country-based mentions of publications in the news and on Twitter

(February 1, 2020 – September 30, 2020).

We then connected the attention paid to the topics covered in both news and on Twitter with the policy responses in the three countries. The patterns of the measures taken differed. In the Netherlands, after an initial lockdown, schools reopened in May 2020, at quite an early stage of the first wave of the outbreak. In South Africa, the outbreak took place in March and schools reopened early in June, just to close again a month later due to the rise of infections, and reopen again in August. In Spain, schools did not open until after the summer holidays.

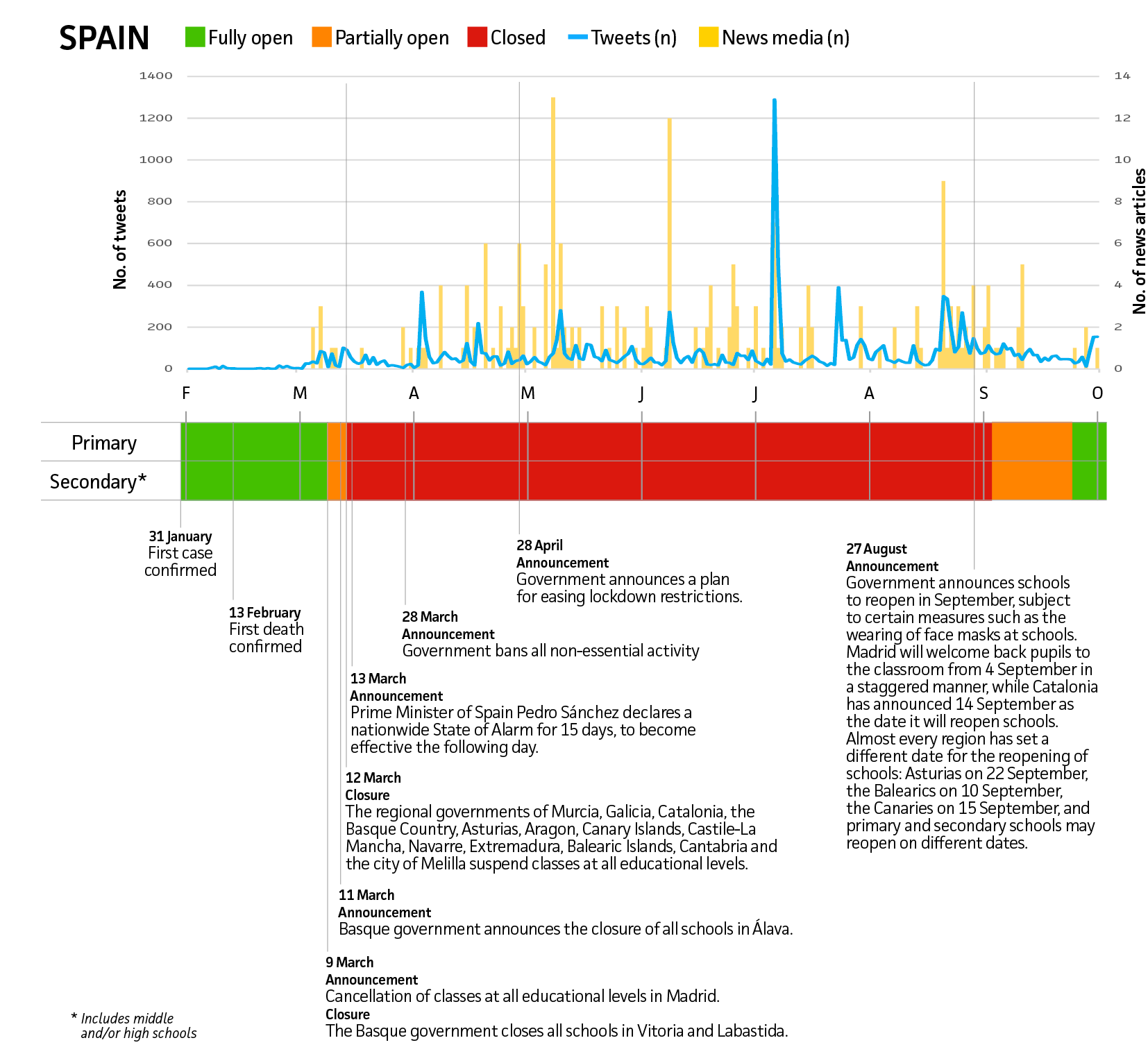

Spain

Figure 1 depicts the announced and implemented measures in Spain as well as the distribution of the news items and tweets originating from Spain. There is a small peak of tweets around the time of the announcements in March, and shortly before and after the schools’ reopening in September. Further activity was registered during the schools’ closure, with peaks around the end of April, when the government announced a plan for easing lockdown restrictions, and also in July and August, when no announcements were made.

Figure 1. Timeline of announcements and implementation of school closure and reopening in Spain, along with the distribution of tweets (on the left y-axis) and news items (on the right y-axis) mentioning scientific articles.

The highest number of tweets in early July revolves around a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study on the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain. A total of 1,906 tweets followed soon after the article was published in the Lancet. The second-highest tweeted article (739 tweets) reports on the paediatric severe acute respiratory syndrome and received distinct attention before the school reopening, as well as again in September. Similarly, attention was paid before the school reopening to the safety of reopening (primary) schools (see here and here).

There are almost no news mentions in March, with sustained but low activity between April and July, and recurrent peaks on specific days at the beginning of May, June, and July. This is followed by more constant activity in the media at the end of August, prior to the reopening of schools. The single-most mentioned article (20 news mentions) received most attention in April. It presents findings on the potential impact of the summer season on slowing the pandemic, weighed against an alternative hypothesis that school closures account for such slowing. The two next most mentioned papers have 17 mentions each. One of them discusses the results of a nationwide screening undertaken in Spain between April and May and concludes that at the time of the survey, there was a seroprevalence of around 5% with lower figures for children (<3.1%) and a third of the positive cases being asymptomatic. The other one focuses on children tested positive.

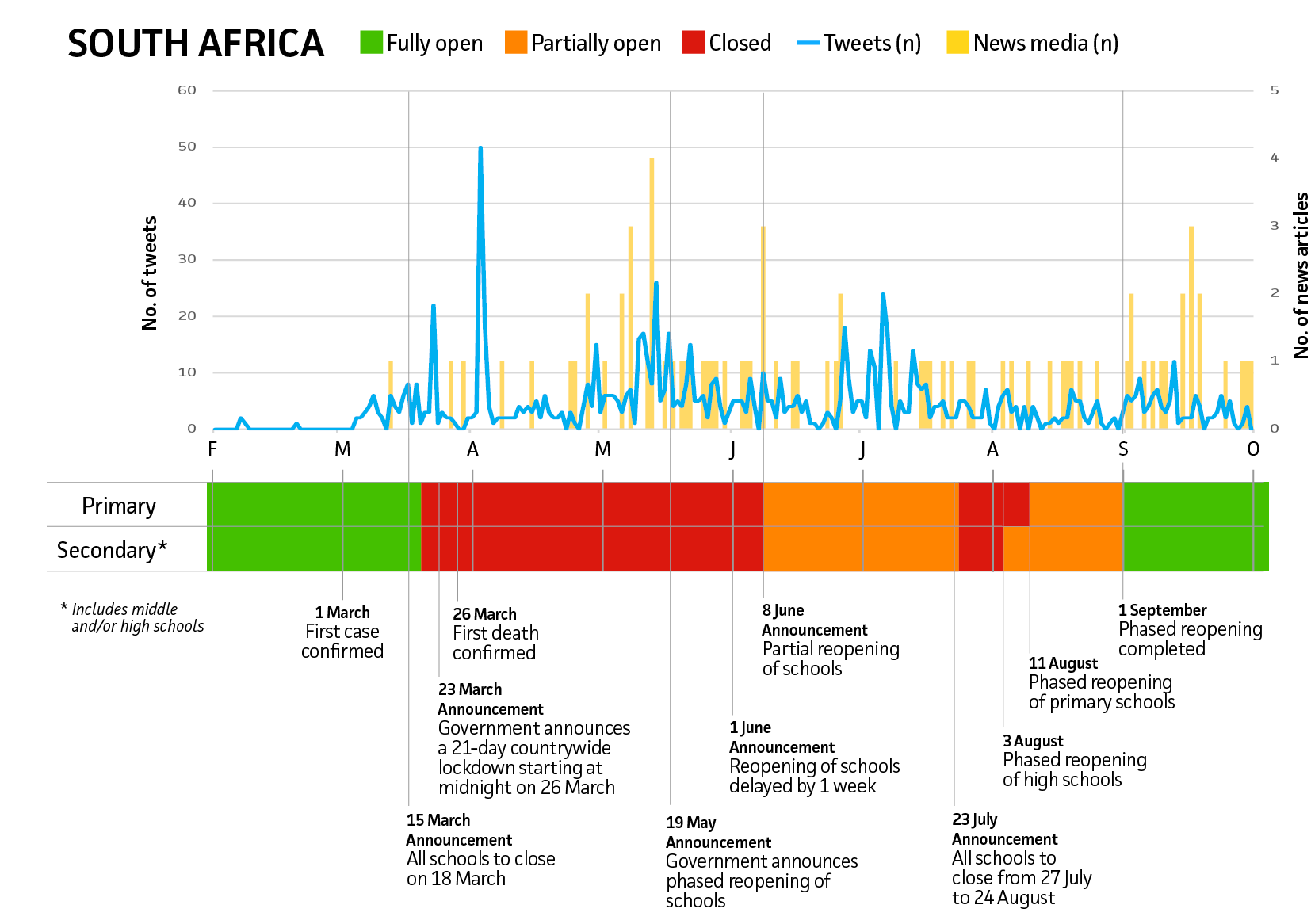

South Africa

In South Africa, there was a notable difference in the reopening of secondary (high) schools and primary schools in July and August (see Figure 2) – primary schools reopened later than secondary schools. Of the 74 news articles originating from South Africa, 33 were published during the first school closure and only 18 in September. The most mentioned studies in the news are again the one on paediatric severe acute respiratory syndrome, and one on large-scale anti-contagion policies. Regarding Twitter, we observe activity around the announcement of school closure in March, and immediately after the first confirmed death, which registers the highest Twitter activity. The highest number of tweets (92 tweets) was sent for a study concerned with the wearing of face masks. The second peak of Twitter activity registered in May around the announcement of a phased reopening of schools reveals discussions gravitating around the Kawasaki-like disease and transmission of the virus by children. Similarly, the discussions from the end of June and beginning of July coincide with the first Europe-wide study of children which suggests mild disease in children and rare fatalities. Second comes the aforementioned seroepidemiological study from Spain (39 tweets).

Figure 2. Timeline of announcements and implementation of school closure and reopening in South Africa, along with the distribution of tweets and news items mentioning scientific articles.

The Netherlands

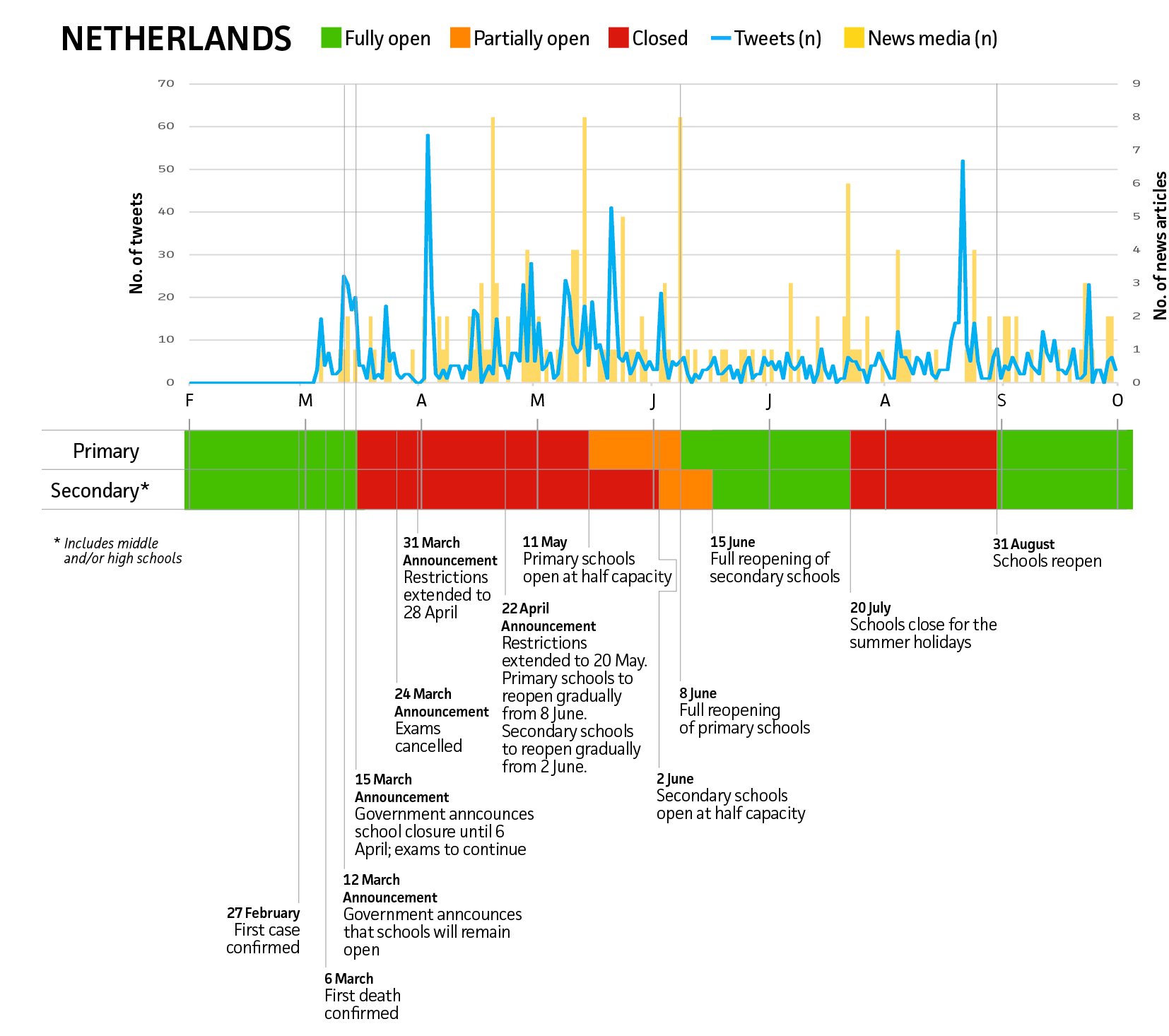

Like Spain and South Africa, the government in the Netherlands decided to close schools in the middle of March. Primary schools were reopened first, at half capacity, whereas secondary schools reopened three weeks later, also at half capacity. The partial opening was short (until June 8 and 15, respectively), after which they were fully open. The second school closure coincided with the summer holidays in the Netherlands (see Figure 3.)

Most news media attention occurred in the period during the school closure and the partial reopening in April and May. Fewer mentions were observed during the summer months, and only 21 were found in September. One study with a relatively high number of mentions to a scientific article (13 news items) reports on the protection through face masks. This is remarkable, as wearing face masks in indoor public spaces was not mandatory until December 2020. In the case of Spain and South Africa, mask wearing was made mandatory earlier, but the news covered this study with only two and one mention, respectively.

Like South Africa, the Netherlands registers relatively modest Twitter activity. The first sustained discussion on Twitter was stirred up by the announcement on March 12th that schools would remain open. The tweets debated the official stance that children are less susceptible to become infected. The highest tweeting activity (96 tweets) was generated by the study reporting on the efficacy of face masks. The second-most tweeted article (79 tweets) mentioned paediatric SARS-CoV-2, while the third-most tweeted one (71 tweets) is a news piece in Nature, discussing scientific support for the wearing of face masks. In mid-May, a systematic review of the literature on SARS-CoV-2 clusters linked to indoor activities caught the attention of Dutch tweeters. The discussion revolved around the need for outdoor sports (for children).

Figure 3. Timeline of announcements and implementation of school closure and reopening in the Netherlands, along with the distribution of tweets and news items mentioning scientific articles.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest national differences regarding the research that was prominently discussed in the news and on social media. This suggests diverging priorities in the public discussion, even during a pandemic, and underlines the importance of considering national contexts when analysing the communication of science.

We also identified a disconnection between the timelines of measures and the intensity of communication of science in the channels observed. The reaction to policy moments was not necessarily accompanied by interest in related scientific output. Attention on Twitter – except for some weak evidence from the Netherlands – was in most cases triggered by the publication of a scientific article, and not a policy event. It is conceivable that this mirrors the interests of the tweeting population – such as researchers or health professionals.

This might also be a reason for the moderate activity on Twitter, with, for example, no particular social movements advocating for a certain position and using scientific information accordingly (as can be observed in the case of the anti-vaccination movement). Also, no highly active Twitter accounts could be found. There were only two accounts (both from Spain) which tweeted more than 100 times during the eight-month period observed (one of them belonging to a paediatrician, the other one to the Spanish Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases). It seems that Twitter was not (mis-)used as a communication platform to amplify ideologically driven messaging, at least in this context. In the case of the news media analysed, we identified several cases of miscommunication of scientific information, which illustrate that the intricacies of scientific studies are not always accurately communicated in the media.

In conclusion, these findings point to the need for further research into the communication of science in specific (national) contexts and across multiple communication platforms during a pandemic. If you are interested in finding out more about our work, please read our recent preprint. It includes, among other details, visualizations of the terms extracted from the articles in our study and a more in-depth exploration of the patterns of news attention and Twitter activity.

The work presented in this blog post has received funding from the TU Delft Covid-19 response fund. Also, we would like to thank Altmetric for providing access to data on news and Twitter mentions.

0 Comments

Add a comment